Drugs we can’t get: S1

There are a number of interesting drugs used in the global market that, for one reason or another, do not have FDA approval and are therefore inaccessible in the US, at least outside of clinical trials. S1 is one of them: a better capecitabine.

What is S1?

S1 is the muy sexy common name of a drug manufactured by Taiho Pharmaceutical in Japan. (It did get a brand name a few years after it went to market: “Teysuno”).

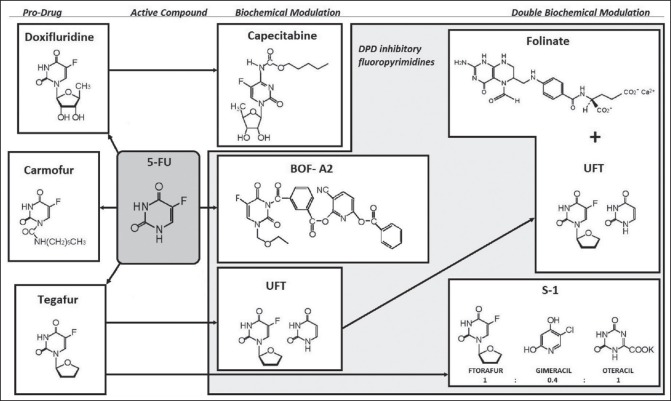

It is a combination of three drugs, all in a pill.

The first is a prodrug, called tegafur or ftorafur (“FT” in many papers), that converts to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in the body. Capecitabine, the only oral 5-FU agent we use in the US, is also a 5-FU prodrug.

The second is gimeracil, a drug that inhibits the enzyme dyhydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD). This reduces tegafur breakdown in the GI tract, which allows it to make its way into the bloodstream. (Patients with inherent DPD deficiency cannot break down drugs in this family once they make it into the bloodstream, leading to potentially lethal side effects from 5-FU and it’s cousins - gimeracil is only creating a local DPD deficiency in the gut. Brilliant.).

The third is oteracil, which prevents 5-FU activation in the GI tract, reducing off-target local adverse effects (capecitabine has horrible GI side effects in many patients). Also brilliant.

This is a very rationally conceived drug. Using a prodrug with a companion that lets it survive long enough to be absorbed lets us use an oral formulation. Oral is so much more convenient than a pump the patient has to wear for a couple of days (and which sometimes malfunctions in strange ways). In capecitabine we already have an oral 5-FU agent that works. However, many of the adverse effects of capecitabine are local to the GI tract, leading to dose reductions or drug switch in many cases, so combining something like capecitabine with something that reduces badness in this location also makes a lot of sense.

This rationality bears out in clinical practice as well (this is not always the case - a popular saying amongst clinical trialists is “the road to hell is paved with biological plausibility.” The majority of ideas that work out well in a petri dish or animal model do not work out at all when we try them in humans. Hence clinical trials.). Trial after trial have established S1 as the standard of care in many relevant regimens in Asia, pretty much any situation where we would use infusional 5-FU or capecitabine in the US. (I’m sure there’s nuance here, but it appears generally true.) S1 works well, is easier to give, and is better tolerated.

So why don’t we have it in the US?

Good. Question.

It’s not that it has been completely ignored by researchers in the West, as you’ll see. The Europeans can get it. And I’m sure Taiho would love to expand their market to the US.

Truthfully, I can’t say I know all the reasons. These things are complex and the FDA’s reasons are not always readily apparent or written clearly (though they often are - I have equally strong respect and disdain for that particular agency, but the trend in my feeling is toward respect. I used to feel only disdain. The more I learn what and how they do All The Things, the more I see a bunch of humans really trying to do their best, rationally to the extent possible, in difficult situations, with many conflicting interested parties).

The clearest reason that S1 is a Big Deal in Asia but unknown here is a difference in the prevalence of certain versions of enzymes that convert the tegafur to 5-FU.

Aside: I’m going to use the terribly imprecise terms “Asian” and “Westerner.” The studies in this area use the terms “Asian” and “Caucasian,” which is worse, as in, “even more wrong than the alternative I chose.” There is huge genetic and biologic variability within and across the places we call “Asia” and “The West,” and, if humans do anything, humans migrate. This biped was made for walkin’, and that’s just what it do. Don’t take these terms too seriously.

Folks from Asian countries tend to have a set of CYP2A6 polymorphisms that lead to much slower conversion of this particular drug, or, more appropriately said (Taiho is a Japanese company, after all), Westerners tend to have a CYP2A6 reality that makes them convert tegafur too damn fast. Dose-finding studies correspond well with the known differences in enzymes: the recommended daily dose in Asia is 40mg/m2 twice a day, whereas the Western dose is 30mg/m2 twice a day.

There are other findings from the dosing studies that don’t precisely line up with differences in processing after absorption. The most severe toxicity in Asian populations is bone marrow suppression, whereas it is GI toxicity in Western populations. I don’t know why the oteracil doesn’t pull its weight in the guts of Westerners. Then again, it might be entirely unrelated to oteracil, I have no idea.

The Dutch, as usual, are leading the way

The most interesting study to-date using S1 in Westerners was done in the Netherlands and published as the “SALTO Study.”

(S1 has approvals in Europe, though for a much shorter list of indications compared with Japan and China, so folks governed by the EMA can get it and play around, whereas there is no provision at all for getting it in the US outside of clinical trial - it has orphan designation but is not approved for anything)

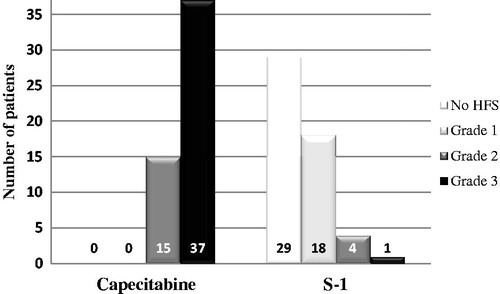

They looked at 161 patients who qualified for 5-FU-based monotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Combination drug therapy is the standard of care frontline therapy in the metastatic setting, but monotherapy is a reasonable option for older and more frail patients, which is who this trial enrolled. They were randomized to S1 vs capecitabine, and compared efficacy as well as rates of adverse effects. Efficacy was comparable, and most adverse effects were also comparable, with the notable exception of hand-foot syndrome. The rates of this were 45% in the S1 group, vs 73% in the capecitabine group. They were also better able to maintain dose intensity in the S1 group, which is a good surrogate for the je ne sais quoi of all the little things that being on therapy does to a person but aren’t fully captured in the other metrics. Though hand-foot syndrome is not a lethal problem, it can be a huge quality-of-life problem, particularly when the point of therapy is palliative in the first place.

The same group also published a retrospective on 52 patients who had hand-foot syndrome on capecitabine and were switched to S1, which they then tolerated beautifully. The graph below is from this paper. “Before” is on the left, and “after” is on the right. The difference is stark.

Why I’d love to have S1 in the US

One tough part of my job is telling somebody who wants to continue therapy but isn’t tolerating the “easiest” form of therapy, even after dose reduction and maximizing supportive care, that their only options are to continue to push forward with the poorly tolerated therapy (to a degree - I’m not afraid to say no and refuse to prescribe if I feel like I’m hurting someone), or stop cancer-directed therapy altogether. I love hospice and the services it provides, and many patients are relieved to make this move, but a significant portion are not. Having another option in the armamentarium, something else to try for the patient who wants to try something, especially in such a commonly used class of drugs, would be great. S1 has clear benefit for patients who have an indication for 5-FU-based therapy but have developed significant hand-foot syndrome, and I would use it in this situation if I had it on formulary.

Also, though I practice in “the West,” not everyone here hails from the Caucasus

“Harumph,” he roared, suddenly on his feet and staring down at me, his tweed’s elbow patches straining as he assumed the pose of a portly academic Superman, “most Caucasians do not, in fact, hail from the Caucasus. Very few do. That was proto-eugenic Neo-Platonic foolery. If you use the term Caucasian, you have to accept the fallacious philosophy upon which it was built, and you are equally obligated to accept the terms from which it is inextricable, namely ‘Caucasoid,’ ‘Mongoloid,’ ‘Negroid.’ Good sir, I do not believe this was your purpose nor desire. If you must use an imprecise term, at least let it be one of the cardinal directions, which are not unladen but are not actively destructive of scientific and societal progress, good sense, morality, and decency.” The final word was given in a whisper.

so having S1 as an up-front option for folks of Asian ancestry would be nice - it’s a clearly better drug in Asian countries, and I doubt it was the ground underfoot that made the difference.

An idea related to this, with perhaps more biological justification than a nebulous definition of ancestry, would be to deploy CYP2A6 screening of some sort to select folks who may most benefit from S1 rather than capecitabine.

This could be done in several ways, all of which have precedence in other types of screening and at some centers. Ideally you’d do trials to determine if any of these actually pan out (see above, on the path to hell). They’re all extrapolations.

One option would be to screen all patients with known Asian ancestry, as is done in some centers for various indications (e.g. GPD deficiency screening for patients of African descent prior to starting potentially problematic drugs).

Another would be to screen only those who have had dose-limiting GI intolerance to capecitabine, to make an argument that perhaps they would tolerate S1 better. (Though, in reality, if S1 was suddenly available and someone’s GI adverse effects were particularly horrendous on capecitabine, I’d probably talk with the patient about it and try it if they want, rather than what I might normally do, which would be to try infusional 5-FU or a drug from a different class, depending on the specifics of the situation. I think an empiric approach would be appropriate, as it wouldn’t require fancy testing which may or may not actually be predictive, and is what we do most of the time with other cognate drugs, even if they have class-effect toxicities - some folks just tolerate Drug A better than Drug B).

A third option would be to screen everyone to try and find folks with compatible CYP2A6 to select for up-front S1. This is expensive. Only fancy places do population-wide pharmacogenomics (etc.) in practice, and there are deep debates about how much good this actually does. But hey, cool if you can get it, especially if you have data to back it up, but even then make you’d have to make sure you don’t take it without a grain or six of salt.

As it is, even if I wanted to test out some of these ideas, or see if the Dutch prospective study replicates, I’d have to go through an insane approval process, and it would be expensive and time consuming. If the drug was approved and available, studies like the Dutch retrospective become almost trivially easy.

One day. Maybe when the Big Boss of the FDA starts reading my blog and sends me a golden goose for my genius, along with a Christmas basket full of S1 and Cadbury. (That’s how it works, right?)

Until next time

This kind of thing is one of my favorites, a thoroughly enjoyable line of inquiry - what drugs are out there that I can’t get? What inspiration is there to be had from the practice patterns of other countries? Would those drugs and patterns work here - why or why not?

It pairs nicely with my obsession with the histories of therapies for cancers. Love me a critical genealogy,* love me some heteroglossia and unfinalizability. Butler and Bakhtin ftw.

* I idly wondered if there had been much movement on that term, which I got at least thirdhand from Judith Butler, and it looks like there’s going to be a cool book coming out in the next year or two: A Genealogy of Genealogy